The Lungwort

The history of lungwort, how they differ from a horcrux, and why their flowers change colors.

Pulmonaria, ‘Spot On’

“Well, you split your soul, you see,’ said Slughorn, ‘and hide a part of it in an object outside the body. Then, even if one’s body is attacked or destroyed, one cannot die, for part of the soul remains earthbound and undamaged.’”

The history of magic, in the ancient and ritualistic sense, is the history of science, but in reverse. It was the tool of the day for explaining the unanswerable and invoking the impossible. But as enlightenment and analytical rigor grew more robust, magic as an explanatory narrative faded. For believers, there were two mystical pathways governing all magic; these they called contagion and sympathy. Contagious magic was based on the thinking that things or persons once in contact can afterward influence one other indefinitely. J.K.Rowling’s Voldemort famously leveraged contagious magic to craft seven horcruxes, in an effort to smite the Boy Who Lived, Harry, and secure almighty power. For the faithful, muggles and wizards alike, life must have been an existence of anxious paranoia, as every stray hair or clipped fingernail could be the source of some soul crushing bewitchery or other.

Poster celebrating The making of Harry Potter, Warner Bros Studio, London, 2013

Sympathetic magic, on the other hand, embraced the notion of ‘like produces like’, or the Law of Similarity. The voodoo dolls of Haitian folk tradition, as an example, relied on sympathy. In other words, if two unrelated objects bore any sensorial resemblance (look, taste, smell, etc), then one could influence the other.

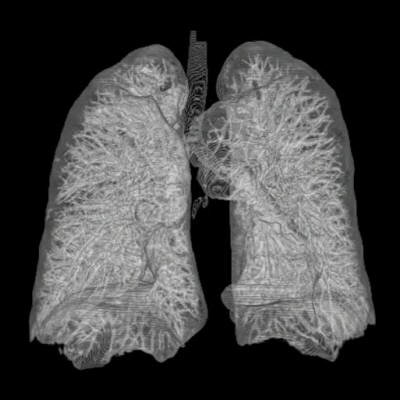

Through these magical tenets, early medicine was born. The Greek physician Dioscorides (mentioned earlier in our discussion of the Hellebore) championed one of the earliest formalized medical philosophies founded on these Laws of Similarity. His presumption, upheld in various forms since ancient times, theorized that the resemblance of a plant to a human organ correlated with its ability to cure diseases of that organ: walnuts, with their brain-like appearance, would strengthen the brain and liverworts, with their liver-shaped leaves, would cure jaundice, and so on. Called The Doctrine of Signatures, it held pharmaceutical sway for more than a millennia and a half. The 17th century botanist William Coles proposed that God made “Herbes for the use of men, and hath given them particular Signatures, whereby a man may read the use of them.” In my garden, the most striking and obvious signature is that of the Pulmonaria, commonly known as Jerusalem-sage, Jerusalem cowslip or most applicably, lungwort.

Human Lung, 3D reconstruction from CT-scans

Pulmonaria is a genus of flowering plants in the family Boraginaceae, native to Europe and western Asia. They are evergreen and herbaceous, forming clumps or rosettes above ground with slowly creeping rhizomes or adventitious roots underneath. Lungworts are covered with bristly stiff hairs and their leaves display prominently the characteristic spots from which their beguiling similarity to our pulmonary tree is begat. Across the internet it is suggested that: “The spots are due to the presence of foliage air pockets. These pockets, which cool the lower leaf surface, mask the presence of chlorophyll.” All such reports derive from a single source: Tony Avent’s “Pulmonaria - The World of Lungworts” for Plant Delights Nursery. Tony, in turn, sites one Marsha Bennett in her 2003 “Pulmonarias and the Borage Family,” which I do not currently have access to. So it remains to be seen how much validity can be thrust onto this single compelling theory for the presence of spots.

The scientific name Pulmonaria is derived from Latin pulmo, meaning lung, as in pulmonologist or pulmonary fibrosis, and was once (according to the doctrine) believed by to be an effective remedy for treating lung diseases. Indeed, the spotted oval leaves of P. officinalis were sold as a remedy for anything airway related, from whooping cough to asthma. Officinalis means ‘sold in shops’. The ‘wort’ (from lungwort), means simply: ‘plant’.

“Nevertheless, one whose lung is swollen so that he coughs and can hardly draw a breath should cook lungwort in wine, and drink it frequently, on an empty stomach. He will become well.”

Pulmonaria officinalis in private garden, Szczecin, Poland

But as scientific rigor waxed, magical thinking waned. Today we know there is no benefit to ingesting Pulmonaria for the purposes of airway disease. Despite that, it is still grown widely and enthusiastically, but more for its shady springtime beauty and hearty disposition than for its curative prospects.

The 5-petal flowers begin early as red or pink but gradually turn blue-purple, as changes in the internal pH modify the alkalinity of the pigment anthocyanin (encountered previously in Siberian Squill). Blooms appear in late March or early April in northern regions, earlier in warmer regions and last for a few weeks. The famous spotted leaves serve as primary grazing for the caterpillars of the moth Ethmia pusiella, who, it must be said, as far as we know live a life free of pulmonary ailments.

Ethmia pusiella

Knowledge Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulmonaria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sympathetic_magic

https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=359968

https://blog.metmuseum.org/cloistersgardens/2013/04/26/lungwort/

https://www.loststory.net/nature/lungwort

https://www.plantdelights.com/blogs/articles/pulmonaria-lungworts

https://www.morrisarboretum.org/blog/plant-names-tell-their-stories-pulmonaria-spp-lungwort

https://www.midwestgardentips.com/perennial-index/pulmonaria

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/downloads/planteval_notes/no17_pulmonaria.pdf

https://www.gbif.org/species/5660579

https://www.palomar.edu/anthro/religion/rel_5.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(supernatural)

https://www.etymonline.com/word/magic

Pearce, J.M.S. (May 16, 2008). "The Doctrine of Signatures" (PDF). European Neurology.

Image Sources

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thorax_Lung_3d_from_ct_scans.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pulmonaria_officinalis_kz01.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethmia_pusiella#/media/File:Britishentomologyvolume6Plate412.jpg