The Flowering Almond

The story of the flowering almond, why some vegetables are fruits, and why pistachios aren’t nuts.

Prunus glandulosa, April 13th

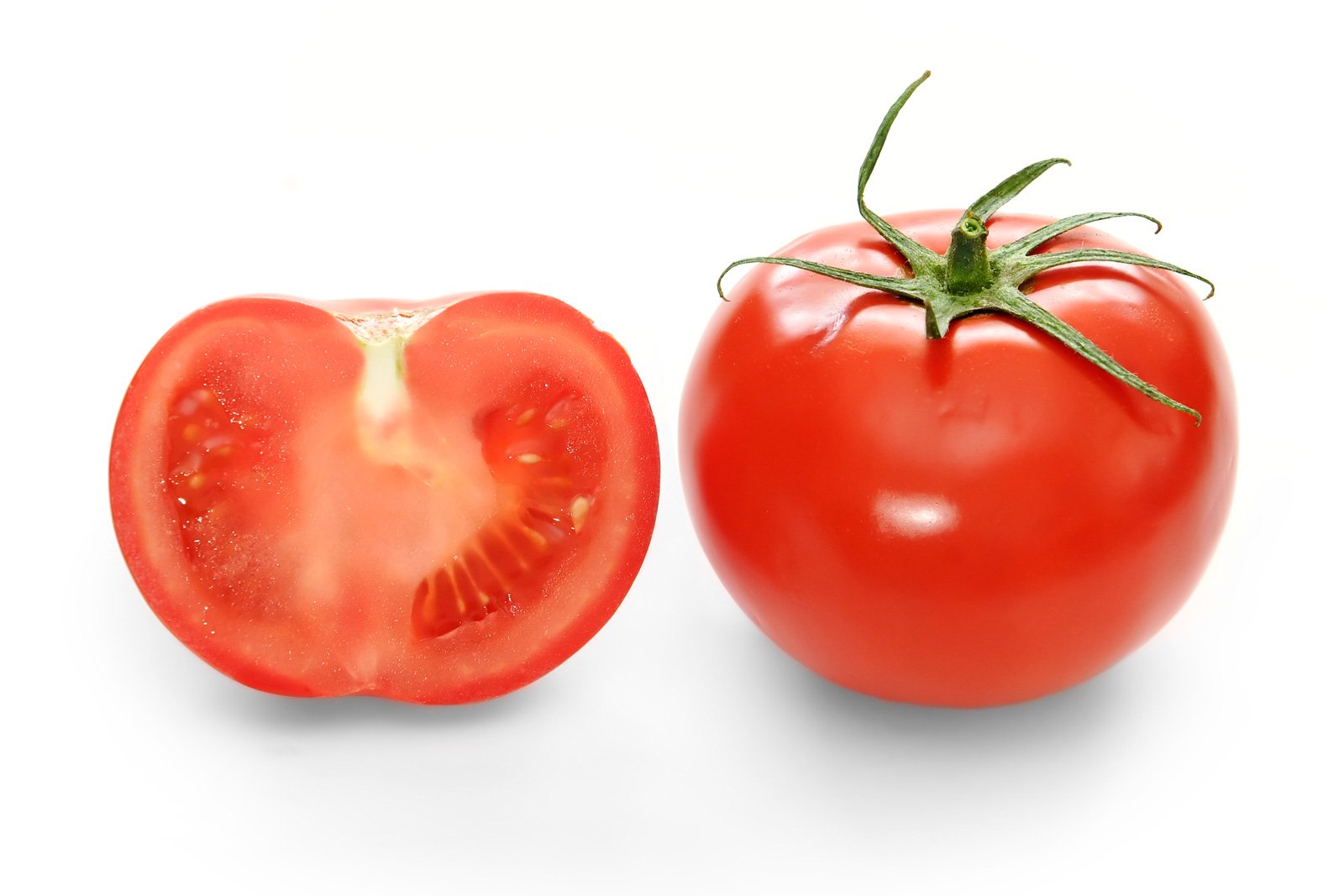

Most of us have heard that the tomato, nearly always tucked amongst other vegetables at markets and in stores, is actually a fruit. This is true, botanically speaking. A fruit is the seed bearing appendage of any flowering plant. In fact, many of what we call vegetables are indeed fruits: beans, peas, eggplant, chili peppers, cucumbers, and avocados are all fruits. Confoundingly, this does not make them not vegetables. The tomato’s horticultural status was so contentious that in 1893 the Supreme Court had to weigh in and settle the issue for concerned marketeers (Nix v. Hedden). They ruled that, at least for purposes of taxation, the tomato is a vegetable. The word vegetable was first recorded in English in the early 15th century. It comes from the medieval latin ‘vegetabilis’ meaning “growing” or “flourishing”, and was originally applied to all plants; the word is still used in this sense in biological contexts today, as in ‘animal, vegetable, or mineral’. In 1767, the word was specifically used to mean a "plant cultivated for food, an edible herb or root". It wasn’t until the year 1955 that we saw the first use of the shortened “veggie". Generally speaking, the way the word is used in modern context conveys principally culinary and cultural (rather than scientific) delineation.

Cross section of a tomato with its seeds.

I bring to bear the vexing vegetal state of the tomato only to make the point that much of the divisions we ascribe to food stuffs is arbitrary or in some cases simply wrong. Consider today’s submission: the Prunus glandulosa. It is a small, multi-stemmed shrub that typically grows about 4’ tall and roughly 3’ wide. It has a tendency to get a bit gangly over the years and benefits well from heavy pruning bi-annually. Where I live, most call it the flowering almond. Elsewhere it is a Chinese bush cherry or Chinese plum. It is native to northern and central China and Japan and produces a small dark red subglobose fruit that resembles neither an almond, cherry, or plum. Well, maybe a cherry a little bit. In any case, it is not to be confused with the closely related but botanically distinct Prunus amygdalus, or true almond.

Notwithstanding this discrepancy, these common names are not entirely off the mark. The genus Prunus includes (among many others) the fruits plum, cherry, peach, nectarine, apricot, and, yes (a bit unexpectedly), almonds. Prunus comes from Latin prūnum meaning ‘plum’. Syracuse University professor Sam Van Aken leveraged the genetic similarity of the genus to graft the so called Tree of 40 Fruit; producing forty edible fruits sequentially from July to October. While many of us would be quicker to label an almond a vegetable rather than a fruit, scientifically it is the latter. “Hold on,” you say, “It’s neither fruit nor vegetable—it’s a nut.” Well, it’s not that either. A nut is a fruit consisting of a hard shell protecting a kernel (which is usually edible). In common parlance and in an epicurean sense, we refer to a number of dry seeds as nuts. Regardless, in a botanical context, "nut" implies a rigid outer shell that does not open (this is called indehiscence) as well as the nutmeat within. No shell = no nut. Hazelnuts, chestnuts, and acorns are true botanical nuts. Pistachios, cashews, and even coconuts (along with almonds), are actually the seeds of a drupe. Peach pits, olive pits, and cherry pits are also seeds of a drupe. A drupe can also be called a stone fruit, which may feel more familiar.

Sam Van Aken’s Tree of 40 Fruit

So, this leaves us in the awkward place where tomatoes are legally, but not botanically, vegetables, peanuts and lima beans are definitely fruits, and almonds are not nuts. In fact, an almond has more in common phylogenetically to the rough and inedible center of an apricot than the deliciously flavorful hazelnut. As mentioned earlier, the flowering almond does not produce the amygdala shaped seeds that make the Mounds alternative so joyful. Its drupes are more decorative than practical. The real value of Prunus glandulosa is the delightfully puffy whitish pink, often double, rose-like blooms that brighten sunny spring gardens. Like all members of the genus Prunus, it is in the Rosaceae family, after all. Its flowers are so similar to some roses, in fact, that I originally used the wrong photo for this article. And on that final word of confusion, we shall leave the flowering almond and turn next to Iran, where humans first cultivated the tulip.

Prunus glandulosa (left) and Rosa ‘The Fairy’ (right)

Knowledge Sources

https://doi.org/10.1002%2Ftax.602021

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tree_of_40_Fruit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prunus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prunus_glandulosa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nut_(fruit)

https://www.businessinsider.in/14-vegetables-that-are-actually-fruits/articleshow/64640693.cms

https://www.businessinsider.com/tomato-fruit-or-vegetable-2018-5

Image Sources

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bright_red_tomato_and_cross_section02.jpg

https://inhabitat.com/amazing-multicolored-tree-produces-40-different-kinds-of-fruit/sam-van-aken-tree-of-40-fruit/