The Fritillaria

The history of Fritillaria, how it influenced medieval European art, and the mystery of a forth Shakespearean portrait.

Fritillaria meleagris, April 7th

Before launching one of the most lasting and memorable careers of our recorded history, William Shakespeare began creative authorship not as a playwright, but as a poet. He excelled at it, to say it with some restraint. Venus and Adonis, a minor epic poem written as a young man and sent to press around 1593, was much celebrated in its day; while living, it was his most popular published work. The poem has enjoyed such lingering notoriety that it shows up still, some 430 years later, in the most unexpected of places— as in the title of Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion theme song--Grim Grinning Ghosts, taken from this stanza:

“Hard-favour'd tyrant, ugly, meagre, lean,

Hateful divorce of love," thus chides she Death,

Grim-grinning ghost, earth's worm, what dost thou mean

To stifle beauty and to steal his breath,

Who when he liv'd, his breath and beauty set

Gloss on the rose, smell to the violet?”

-William Shakespear, Venus and Adonis (c. 1593)

Singing Busts in The Haunted Mansion at Disneyland, California

We have encountered the tale of Venus (or Aphrodite to the Greeks) and Adonis previously, in the history of the Anemone, two blooms past. One striking deviation in Shakespeare’s iteration was the use of a ‘purple flower sprung up, chequer’d with white’ to honor the deceased Adonis, rather than the classic daisy-like anemone. Fritillaria must have been the species referenced—it could hardly be another. There is no other flower quite like it. It was, and is, robustly common in his part of the world. The genus name comes from the Latin fritillus, referring to an ancient checkered roman dice box. The checkered fritillary butterfly gets its name from same. So, within one month of blooms, we have two disparate flowers springing forth from the same lost mortal lover of Venus.

By this, the boy that by her side lay kill’d

Was melted like a vapour from her sight,

And in his blood that on the ground lay spill’d,

A purple flower sprung up, chequer’d with white.

-William Shakespear, Venus and Adonis (c. 1593)

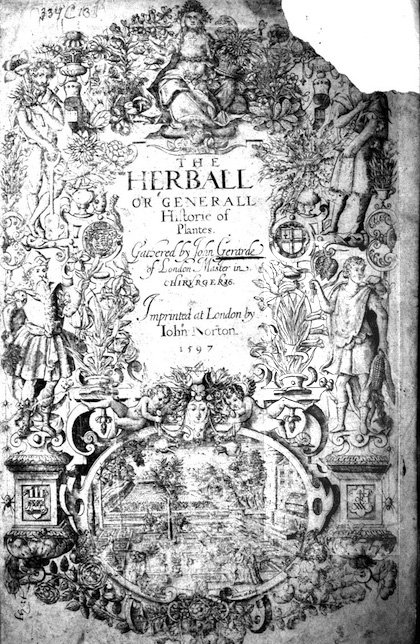

Title page of The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard (1597).

It was in this setting that, on May 20th, 2015, Country Life Magazine made the astonishing pronouncement that a new likeness of William Shakespeare had been discovered. Botanist and historian Mark Griffiths, on the title page of a 400 year old gardening text (The Herball, John Gerard, 1597), noticed four figures of whom three were presumed known. According to The New Antiquarian: “Three of the four figures appear relatively straight-forward and uncontentious: the author himself, his patron -- Lord Burghley (who raised Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford and for many the prime suspect for who could have written the Shakespeare plays if William did not), and Rembert Dodoens, the Flemish botanist whose work Gerard was building upon. The fourth figure is less obvious, and this is the one Griffiths believes to be William Shakespeare.”

Two suppositions support Griffith’s argument. The first regards what is known as a rebus—an ornamental device associated with a person to whose name it punningly alludes. The plinth on which the fourth figure stands is engraved with a mark that Griffith has proposed to be said ornamental device. His decryption intended to resolve this rebus (presented here) is… involved.

The second concerns the flower. The figure in question holds a flower with which he must, says Griffith, have some defined and particular connection. It is the uniquely checkered and impossible to mistake fritillaria that caught his attention and is alleged to directly reference Shakespeare’s deviation from the classical Anemone in Venus and Adonis.

Detail of suspect figure from title page of The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard (1597).

While all of this may sound of little consequence, it’s a declaration of substantial heft. The authors of Country Life boast the new image of William Shakespeare is “the first and only known demonstrably authentic portrait of the world’s greatest writer made in his lifetime.” Bear in mind that, to date, every physical feature we know about the most venerated figure in the English language comes from only two post-humous likenesses, the copper plated Droeshout engraving that appeared on his first folio 7 years after his death and a life sized statue that forms the centerpiece of a monument to Shakespeare in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon. A number of other works, such as the Chandos and Cobbe portraits, have been suggested as Shakespeare, but retain no provenance to solidify them as factually so. Thus, when Griffiths professed to have found a third, scholarly heads turned.

So did the humble fritillaria point us to a new Shakespearian likeness? The concise answer is: probably not. A fritillary, being unique and recognizable, would not be an odd choice for the title page of a botany text and the assumed rebus is much more likely a printer’s mark, in this case for John Norton. Who is the figure then if not Shakespeare? John Overholt, Curator of Early Modern Books at the Houghton Library, suggests "One excellent candidate is the Greek botanist Dioscorides; as one of the ancient founders of the field, he’s a logical choice to represent on the title page of this book." In fact, as Rick Rennick points out: “the second edition of The Herball (1636) appears to make the identity plain, with Dioscorides being helpfully named in the lower-right position.” To read this in more depth, see Rick Rennick’s article in The New Antiquarian here.

Fritillaria meleagris is a spring flowering herbaceous plant in the lily family, commonly called the snake’s head lily, from the nodding posture it adopts on a windy day, or checkered lily, from its binary chess board patterning. It is a bulbous perennial that is native to river flood plains in Europe where it is frequently seen growing in large colonies. Fritillaries were a favorite of the Dutch flower painters Ambrosius Bosschaert and Jacob de Gheyn II, who emerged in the early 1600's, and appeared in Italian art, such as that of Jacopo Ligozzi in the late sixteenth century. Like lilies and irises, they were commonly employed in the use of floral emblems, such as for various Coats of Arms.

A Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Flask on a Marble Ledge, Flanked by a Red Admiral Butterfly and a Lizard, Ambrosius Bosschaert, 1607

Coat of arms of Großsteinbach, Styria

There are over 130 species of Fritillaria. Some, like the meleagris, are considered nearly invasive in places, whereas others are almost unknown. The Fritillaria gentneri is one of the rarest native plants in the world. It is found only in isolated populations in Southern Oregon. Several species originate east of Europe and have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for over 2,000 years. Unlike other folk remedies, their use is not entirely unfounded. In one study, fritillaria reduced airway inflammation by suppressing cytokines, histamines, and other compounds of inflammatory response. The production of medicines from F. cirrhosa, as an example, is today worth US$400 million per annum.

Knowledge Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritillaria

https://theheartthrills.com/tag/fritillaries/

https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-the-month/fritillary.shtml

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/fritillus#Latin

https://www.abaa.org/blog/post/shakespeares-face

https://jvwoodlands.org/the-fritillaria-story/

https://gutenberg.ca/ebooks/sackvillewestv-theland/sackvillewestv-theland-00-h.html

https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/venus-and-adonis/

https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=281768

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56962/venus-and-adonis-56d239f8f109c

Image Sources

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Disneyland_Haunted_Mansion_Singing_Busts.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ambrosius_Bosschaert_-_A_Vase_of_Flowers_290N10007_B3PLD.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AUT_Großsteinbach_COA.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=the+herball&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image