The Euphorbia

The history of the Euphorbia, how two men discovered dephlogisticated air, and why we all evolve toward similar goals.

Euphorbia polychroma, 'Bonfire', April 24

“The whole history of inventions is one endless chain of parallel instances. There may be those who see in these pulsing events only a meaningless play of capricious fortuitousness; but there will be others to whom they reveal a glimpse of a great and inspiring inevitability which rises as far above the accidents of personality.”

Joseph Priestly

Less than half a year before General Thomas Gage ordered troops to seize military supplies in Concord, Massachusetts, igniting the first shots of the American Revolution, a humble clergyman across the pond was producing isolated oxygen gas for the second time in history. His name was Joseph Priestly and to do this was no small task. He began by heating liquid mercury to near boiling for several months, then focusing a beam of laser hot sunlight on it through a 12 inch convex lens. The result, achieved on August 1, 1774, was the production of an achromatic gas which he promptly collected in rudimentary glass vials and began testing. He found the gas to be insoluble in water and vigorously combustible. He proudly christened it dephlogisticated air, (under the mistaken belief that all other air was, obviously, phlogisticated). Priestly was unaware that he had just synthesized an, as of yet, undescribed periodic element, and even more unaware that it had already been done 870 miles away by an unassuming pharmacist named Carl Wilhelm Scheele.

Carl Scheele

Approximately one year prior to Priestly’s discovery, eastward in Uppsala, Sweden, Carl Scheele was helping his friend and chemistry professor Torbern Bergman investigate a mysterious red vapor produced when saltpeter was heated with acetic acid. Scheele selected the unorthodox and brute force strategy of tossing nearly anything he could find into the boil kettle: potassium nitrate, silver carbonate, manganese nitrate, manganese oxide, and mercuric oxide. While the red vapor (nitrogen dioxide) remained elusive, he managed to isolate an odorless tasteless gas that: “supported the combustion of a candle more than air.” He named it feuerluft, or ‘fire air.’ Fortuitously, inadvertently, and unbeknownst to the world, Carl Scheele had forged oxygen gas for the first time.

Joseph Priestly and Carl Scheele never met, so far as we know. There is no evidence to suggest they ever read each other’s works or even knew of the other’s existence. But each, motivated by the prevailing force of intellectual curiosity, isolated and characterized the same novel element at roughly the same time. This phenomenon, independent discovery (sometimes called cultural convergence) whereby ideas, technologies, and systems develop from distant beginnings, often as a result of similar environmental pressures, is surprisingly commonplace. Quite recently, as an example, Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald were jointly awarded the Nobel prize in 2015 for separately finding that neutrinos have mass. Calculus was famously discovered disparately in the 1600’s by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz. The blowgun was conceived both in Southeast Asia and Central America. The techniques of farming and agriculture were developed, without any intercontinental collaboration, in several distinct, disconnected parts of the world, including China, Middle East, and South America many thousands of years ago. But however long it can be said that human cultures have evolved separately toward similar tactics and solutions, nature has been doing it longer. We call this convergent evolution.

Euphorbia jolkin along the coastline of Mageshima, Japan

Euphorbia is a very large and diverse genus of flowering plants, conventionally called spurge. The genus has roughly 2,000 members, which is, to say it with some restraint, a lot. The botanical name Euphorbia is taken from Euphorbos, the Greek physician of Cleopatra’s son-in-law, King Juba II (50 BC – 23 AD). The common name spurge derives from the Middle English/Old French espurge ("to purge”), and is a reference to the intractable disgorgement experienced after ingesting the Euphorbia’s milky white effluvium, often called ‘latex’. For reference, there is no connection between the latex in plants, such as that harvested from rubber trees (like Hevea brasiliensis) for the production of mattresses, balloons, gloves, etc, and synthetic latex, which is a petroleum by-product, used in paints and glues. In fact, there is very little similarity between Euphorbian latex and that of the commercially viable Rubber tree either.

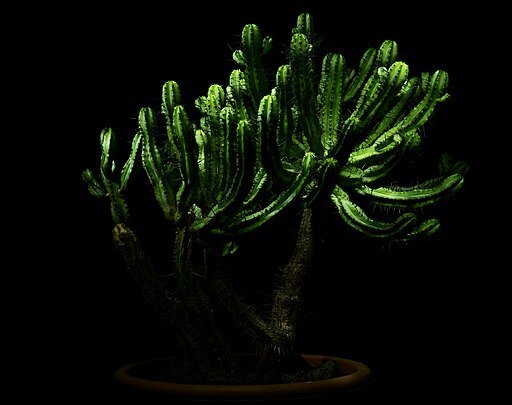

I mean, it sure LOOKS like a cactus. (Euphorbia enopla)

Euphorbia are so diverse that it can be a bit challenging to find any universal characteristics between the species. Some, like the Euphorbia ampliphylla, are massive and long lived trees stretching almost 100 feet skyward while others are short and showy garden additions. Particularly striking are the succulent contingent that have evolved with spines, thorns, a short stubby ground loving habit, and a preference for arid conditions. The confusion of succulent Euphorbias for cacti is so recurrent that a number of websites have devoted pages to distinguish the two. It must be said here that cacti and Euphorbias are not at all related. Rather, it is simply that some Euphorbias have, under similar selective forces, developed nearly identical strategies as the more familiar Cactaceae family. This similarity is a product of convergent evolution; the biological equivalent of cultural convergence, where different species, often unrelated or only distantly related, independently evolve similar traits or characteristics in response to similar environmental challenges. Despite their genetic and evolutionary differences, these species end up advancing analogous features that serve similar functions.

In fact, cacti are distinct in a few seemingly nit picky ways:

Cacti have areoles: those cushiony, fuzzy dots from which their spines, stems and flowers grow.

Cacti produce thorns in clusters, whereas Euphorbia thorns are typically singlets or doublets.

Euphorbias produce the aforementioned milky toxic latex; cacti do not.

Cacti are almost exclusively leafless.

Cacti evolved in the New World (North, South and Central America, as well as in the Caribbean), while succulent Euphorbias evolved in the old (Africa, Madagascar and drier areas of Asia)

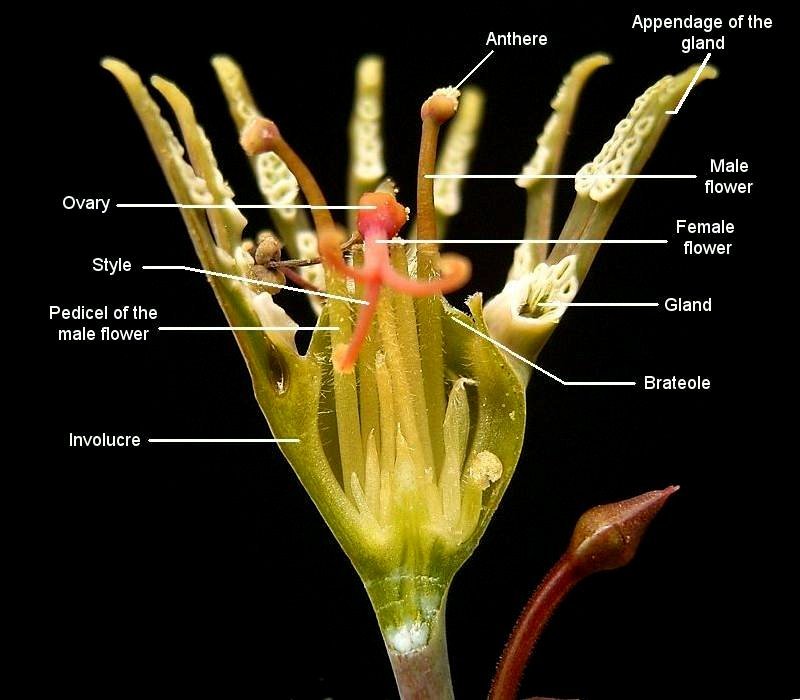

What binds all Euphorbias together, the thing that sets such a diverse group of plants in a genus by itself, is the production of a particularly unique bloom-like apparatus called a cyathium. Rather than a traditional flower, Euphorbias shirk all notion of the usual petals, sepals, carpels, or stamens and make this cup shaped whorl of leaflets enclosing five or so smaller flowerettes instead. They are the only plants in the botanical kingdom to do so.

Cyathium.

Just outside of San Diego is the Paul Ecke Ranch, the largest single producer of Euphorbias in the world, commanding roughly 70% of the global market. It was started in 1909 by Albert Ecke who began cultivating Euphorbia pulcherrima, better known as the Poinsettia or Mexican Flame Flower, in Hollywood before moving his operation to Encinitas. Nearly 70 million Poinsettias are sold in the US each year during the 6 week period preceding Christmas—a cultural icon we have all converged to embrace.

Other Examples of Convergent Evolution in Biology

Echolocation in Bats and Dolphins:

Camera-like Eyes (lens, cornea, retina) in Octopuses and Vertebrates

Gliding in Sugar Gliders and Flying Squirrels

Spines in Echidnas and Hedgehogs

Salt Excretion in Mangrove Trees and Halophytic Plants

Knowledge Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euphorbia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Ecke_Ranch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poinsettia

https://cactiguide.com/cactiornot/

http://www.euphorbiaceae.org/pages/about_euphorbia.html

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Experiments_and_Observations_on_Differen/wAk8qYhsQ0MC?hl=en&gbpv=1

https://qz.com/emails/quartz-obsession/1482596/simultaneous-invention

https://laidbackgardener.blog/2018/09/19/cactus-or-euphorbia/

https://www.britannica.com/science/oxygen

https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/8/oxygen

https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/josephpriestleyoxygen.html

https://education.jlab.org/itselemental/ele008.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxygen

https://www.beautifulchemistry.net/scheele

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Wilhelm_Scheele

https://www.frontiersin.org/news/2022/03/18/children-in-science-carl-wilhelm-scheele-the-forgotten-chemist/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Carl-Wilhelm-Scheele

https://www.britannica.com/science/oxygen

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4633856/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple_discovery

https://homework.study.com/explanation/explain-what-is-meant-by-convergent-evolution-provide-an-example.html

https://www.kli.ac.at/webroot/files/file/Workshop%20booklets/33AWTB_kern_final.pdf

https://study.com/academy/lesson/divergent-convergent-evolution-definitions-examples.html

Image Sources

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_Wilhelm_Scheele.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PSM_V05_D400_Joseph_Priestley.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Euphorbia_enopla_v_české_sb%C3%ADrce.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cyathium_cross2_ies_no_letters.jpg